I moved in with Grandma Doris when I was three days old, and from that moment on, my life took a shape that was both fragile and fiercely held together by love. My mother, Lina, died shortly after giving birth, leaving behind a tiny, red-faced baby and a silence that no one quite knew how to fill. My father never appeared—not once, not for a birthday, not for a school play, not even for a phone call. Grandma used to tell me that my mother held me for three minutes before her blood pressure dropped, and that those three minutes were filled with more love than some people give in a lifetime. I grew up believing that, carrying it like a quiet blessing. Grandma Doris was 52 when she took me in, old enough to be tired but young enough to decide that she would start over for me. She worked nights as a janitor at my high school and mornings as the steady, patient engine that kept our little world running. Our apartment was small, but she filled it with warmth: the smell of coffee and pancakes on Saturdays, the rustle of secondhand novels as she read them aloud from an armchair with torn seams, the hum of old radio songs drifting through the kitchen while she washed dishes. She made everything feel wide and possible even when money was tight. She never once made me feel like a burden—not when I had nightmares and woke her up shaking, not when I cut my own hair with her sewing scissors and came out looking like I’d lost a fight with a lawn mower, not when I outgrew my shoes faster than her paycheck could keep up. To me, she wasn’t just my grandmother. She was a one-woman village, a lighthouse in a stormy sea, and the person who made me believe that even broken beginnings could lead to beautiful places.

That was why I never told her what school was really like. Once people realized that the school janitor was my grandmother, things changed in small, poisonous ways. It wasn’t dramatic at first—just comments thrown around when teachers weren’t listening. “Careful, Lucas smells like bleach,” someone would mutter as I passed. “Mop Boy,” another would laugh. One day someone spilled milk at my locker and taped a note to it that said, “Hope you brought your bucket.” I cleaned it up in silence, swallowing the shame that burned in my throat. I never told Grandma because the thought of her feeling ashamed of the job that kept us fed was unbearable. That job, those long nights mopping hallways and emptying trash cans, was what paid for my books, my lunches, my future. If she noticed something was wrong, she never pressed. I came home smiling, helped with dishes, listened to her stories, and made her laugh on purpose. Our kitchen was my safe place, the only place where the words people used against me couldn’t reach. Still, they stuck. They followed me into classrooms, into the locker room, into my own head. I counted down the days until graduation like it was a rescue plan, a promise that one day I would step out of those halls and into a life where no one would see me as just the janitor’s grandson.

The one bright spot in all of it was Sasha. She was sharp and confident, funny in a dry, sideways way that made even bad days feel lighter. People noticed her looks first, but they didn’t see how she helped her nurse mother juggle double shifts, or how she balanced tip money in a worn yellow notebook, counting every dollar twice to make sure the rent got paid. Her life wasn’t easy either, just quieter about it. That was why we understood each other without having to explain much. She met Grandma Doris once while we were waiting in the cafeteria line. Grandma stood nearby with a tray of milk cartons and her mop leaning against the wall. “That’s your gran?” Sasha asked, glancing at her. “Yeah,” I said. “She looks like the kind of person who gives second helpings even when you’re full.” “Oh, she’s worse,” I replied. “She’ll bake you a pie for no reason.” “I love her already,” Sasha said, and she meant it. Prom season crept up faster than I expected, with people talking about limos, dresses, and after-parties. I avoided the subject until Sasha finally stopped me after class. “So… who are you taking to prom?” she asked. I hesitated. “I’ve got someone in mind.” Her eyebrows lifted. “Someone I know?” “She’s important to me.” Sasha nodded slowly. “Right. Well… good for you.” She didn’t bring it up again, but there was something thoughtful in her eyes that made me think she was guessing more than she said.

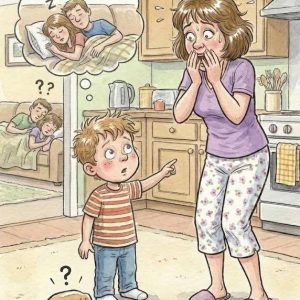

On prom night, Grandma stood in front of the mirror holding a floral dress she hadn’t worn in years. She kept smoothing it like it might suddenly change shape. “I can stay home,” she said gently. “I don’t want to embarrass you.” “You’re not embarrassing me,” I told her. “I want you there.” She looked nervous, like someone attending a party they weren’t sure they were invited to. I helped her with her silver leaf earrings and straightened my tie while she checked the crease of my jacket. The gym looked different that night—string lights, music, laughter bouncing off the walls. Awards were handed out. Sasha won one. I heard Grandma’s warm chuckle from the back of the room, a sound that made everything feel right. When the slow songs started, Sasha asked, “So… where’s your date?” “She’s here,” I said, and walked across the floor to Grandma Doris. “Would you dance with me?” Her hand flew to her chest. “Lucas, sweetheart…” “Just one dance.” We stepped onto the floor—and that’s when the laughter started. “He brought the janitor?” “That’s gross.” “Doesn’t he know prom’s for couples?” Grandma stiffened. Her hand slipped from mine. “It’s okay,” she whispered. “I’ll go home.” Something settled inside me then—not anger, but clarity. “No,” I said. “Please don’t.”

I crossed the floor, walked straight to the DJ booth, and asked for the microphone. The music cut. The room fell silent. “Before anyone laughs again,” I said, my voice steady despite my heart pounding, “let me tell you who this woman is.” I pointed to Grandma. “She raised me when no one else would. She cleaned your classrooms so you could sit in them. She stayed quiet when she could’ve made noise. She is the strongest person I know.” The silence was heavy, thick with something that felt like shame. “And if you think dancing with her makes me pathetic,” I added, “then I feel sorry for you.” I walked back, held out my hand again, and said, “May I have this dance, Gran?” She nodded, tears slipping down her cheeks. Applause started slowly, then grew, rolling through the room like a wave. We danced under the lights while everyone watched—not laughing this time, but listening. Later, Sasha handed me a cup of punch. “For the record,” she said, “best prom date choice of the year.” The following Monday, Grandma found a folded note taped to her locker in the staff room: “Thank you for everything. We’re sorry. —Room 2B.” She kept it in her pocket all week, pulling it out sometimes just to look at it.

That Saturday, she wore her floral dress while making pancakes, just because she wanted to, humming softly as she flipped them in the pan. We sat at our tiny kitchen table, syrup sticky on our fingers, laughing about nothing and everything. For the first time, I knew she’d walk into my graduation not as someone invisible, but as someone seen. The halls that once echoed with whispers would now carry the memory of applause, and the woman who had quietly kept the world running would finally be recognized for the love and strength she had always shown. Our story didn’t end with a dance; it began there, in a gym lit by string lights, where a janitor and her grandson reminded everyone what dignity and gratitude really look like.